Intel Broadwell-E Core i7-6950X Review: The first 10-core enthusiast CPU is a beast

Monstrous. Brawny. Or in the parlance of our times: OP for “overpowered.” All are apt terms for Intel’s new 10-core Core i7-6950X, a muscular CPU so over-the-top in power, that you’d have to be crazy to need one.

But Intel’s Extreme Edition CPUs have never been about catering to practical need. No, they cater to your desire for raw performance.This time, though, Intel is pushing both performance and your wallet to the very edge with a CPU priced at $1,723.

No, that’s not a typo: $1,723. For just one CPU.

For more details on the chip, read Mark Hachman’s deep dive. To find out if Intel’s brutishly powerful chip is worth it, read on.

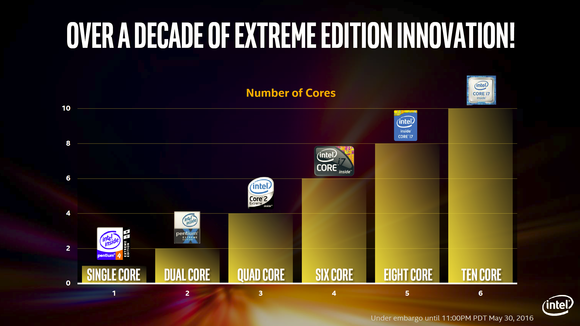

Intel has been pushing the Extreme Edition chips for a decade now but this one may top them all.

No surprises here

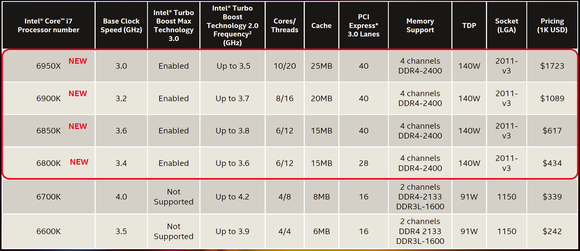

Broadwell-E has probably been one of the worst-kept secrets in the industry. Models and specs leaks have been floating around for months. All those rumors are merely that until we get it from the horse’s mouth, and Mr. Ed has finally spoken. Here are full details on the Broadwell-E product line, including the current two Skylake “K” chips (outside the red box.)

The Broadwell-E family includes four models all of which cost a little more than the Haswell-E chips they replace.

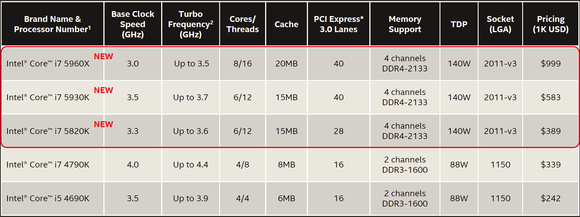

The Broadwell-E family essentially replaces the three Haswell-E family chips, which were introduced two years ago with the LGA2011-V3 platform. Except for the new 10-core Broadwell-E, which creates a new uber-chip tier above the others, the rest fall in line with the older Haswell-E chips they replace. See the details below from the original rollout of Haswell-E with the pair of smaller Haswell “K” CPUs (outside the red box).

Haswell-E introduced a new LGA-2011 V3 platform and 8-cores for “free.”

Besides the new cores, you also get a price increase—a perk of having basically no competition. Intel continues to offer a ”budget” Broadwell-E, which has six cores and fewer PCIe lanes available in the chip. That decision isn’t technical, it’s marketing. If you want to build or buy a PC with 40 PCIe Gen 3 lanes turned on, you have to pay the extra price.

An easy upgrade

On the outside, the new Broadwell-E’s heat spreader gets a more angule design that increases its strength for the more fragile 14nm chip inside. Like Haswell-E, it uses solder interface material rather than thermal paste.

Broadwell-E was always intended as a drop-in replacement for Haswell-E so for the most part (more on this later) there’s no surprises. Just update your BIOS and socket in the chip and you’re ready to rocket. The new chip also supports DDR4/2400 officially, which Haswell-E did not (though it did just fine with that memory anyway).

Intel’s new 10-core Broadwell-E sits in the middle, with an eight-core Haswell-E on the left and an older Haswell quad-core on the right.

Broadwell underneath

The actual microarchitecture inside shouldn’t surprise, either. It’s built on a 14nm process using the Broadwell (5th-gen) cores that have been in laptops since 2015 (late 2014, if you count Core M). Broadwell actually made a very late appearance in desktops in the unwanted Core i7-5775C (which I reviewed) in 2015 before quickly sinking into obscurity when the 6th-gen Skylake CPUs showed up days later.

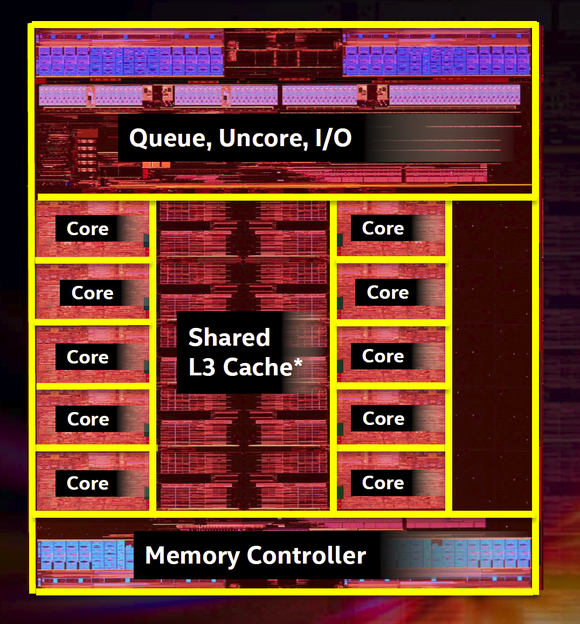

Here’s a shot of the die. As you can see, it’s a native 10-core chip on the highest-end Broadwell-E part. Intel doesn’t pull any funny business by using a chip with 12 cores and turning off two. The 8-core and two 6-core models use the same 10-core chip, with cores permanently switched off.

The Broadwell-E die is a native 10-core part with all of them turned on. That mystery blacked out portion isn’t Area 51. Intel says it’s Xeon functionality that isn’t used.

Turbo Boost Max Technology 3.0

Among the most notable changes to Broadwell-E is the new Turbo Boost Max Technology 3.0 feature.

Turbo Boost was introduced with the first Core i7 chips in 2008. Like the name says, it temporarily increases the clock speed of the chip to improve performance.

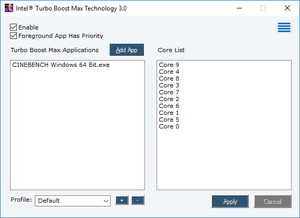

The Turbo Boost Max Technology 3.0 utility lets you set an app to run on the fastest core.

Turbo Boost Max 3.0, exclusive to the Broadwell-E, is quite different. Intel said it identifies at the factory which CPU core is the “best” and runs it at a higher clock speed than the others.

Turbo Boost Max 3.0 can then bind single-threaded applications to that one higher-flying core, for a performance boost of up to 15 percent.

Turbo Boost Max 3.0 can boost apps in the foreground, and it lets you assign a particular app to a particular core or cores.

In Windows, you’ve been able to bind a certain program or process to a particular core or thread by changing the affinity. Turbo Boost Max 3.0 does it for you automatically (once set up).

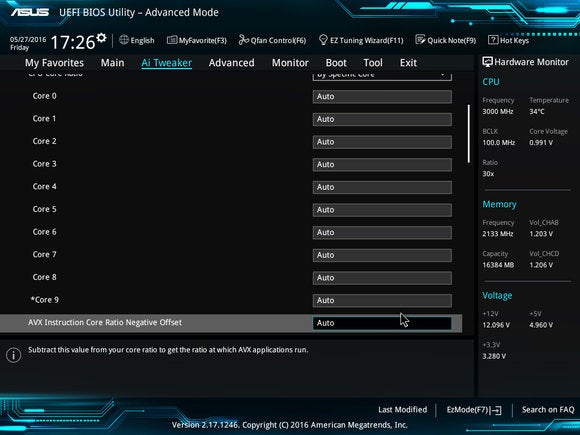

The BIOS of the Asus X99 Deluxe II board shows the list of the cores and the asterisk indicates what is the “best” core of the litter.

Per-core overclocking and more

Broadwell-E has a few features catering specifically to the overclocking sports—nerds who push CPU clock speeds to multi-gigahertz levels using liquid nitrogen and other exotic cooling methods in competition. One feature, for instance, lets you crank back the AVX ratio to lower the power it consumes during benchmark runs.

Not everyone is into extreme overclocking sports, though. Many just want to tune a CPU to its highest actual usable performance. For them, Intel has added per-core overclocking. With older CPUs, overclocks were somewhat granular in that you could pick higher frequencies based on whether it was using, say, two cores. The cores picked, though, were random. With Broadwell-E you can overclock a specific core and even change its individual voltage.

When combined with Turbo Boost Max 3.0, you could, say, set an application to run on that particular overclocked core. That pays real dividends in performance for someone willing to put in the tuning time.

Lots of cores, lower clock speeds

It’s no coincidence that so many of Broadwell-E’s innovations are aimed at giving the chip better performance in single-threaded or lightly-threaded tasks. That’s because Intel knows applications that can take full advantage of the resources of a 10-core chip, or even an 8-core chip, are rare.

That inconvenient truth has always put the company’s big chips at a distinct disadvantage to the smaller quad-cores such as Intel’s Core i7-6700K. With fewer cores and lower thermal overhead, those quad-cores can easily run at higher clock speeds. For example, the same Core i7-6700K has a base clock speed of 4GHz, while the top-end 10-core Broadwell-E has a base clock of 3GHz. All the tweaks Intel has put into Broadwell-E, the company said, should put it on far better footing with a nimbler quad-core, while giving it the capability to blow the doors off when the load needs more than four cores.

Read on for our performance benchmarks and how we tested

Performance and how we tested

Gordon Mah Ung

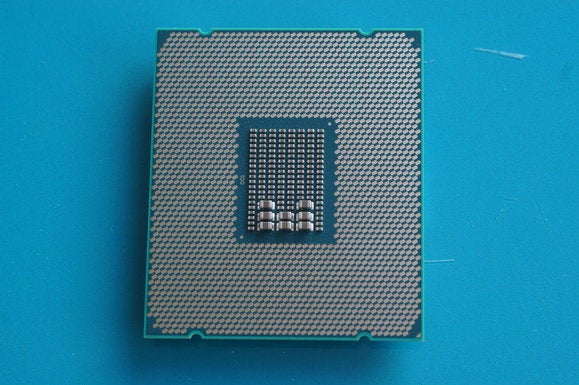

Gordon Mah UngHere’s the backside of Intel’s new 10-core Core i7-6950X chip.

For our performance testing I set up three different systems to test the 10-core, plus three chips that I think should be compared to it: An eight-core Haswell-E Core i7-5960X, a quad-core Skylake Core i7-6700K, and a six-core Ivy Bridge-E Core i7-4960X.

All three systems received clean installs of Windows 10, and each was tested with a GeForce GTX 980 card and duplicate Kingston HyperX Savage SATA SSD. All three also had 16GB of Corsair RAM. We used DDR3/2133 in triple-channel mode for the Ivy Bridge-E system, and DDR4/2133 in quad-channel mode for the Haswell-E and Broadwell-E systems. The Core i7-6700K ran in dual-channel mode.

The Haswell-E and Broadwell-E were swapped into the same system for testing. The latest available UEFI builds were also installed on all three motherboards. Both the Skylake and the Ivy Bridge-E chips used Asus motherboards, while an X99-based Asrock board was used for the Haswell-E and Broadwell-E CPUs.

One big caveat

Before we get too far into the benchmark-o-rama, I’d like to point out that I ran into a snag early on that simply could not be remedied in time to make this story deadline. Intel has maintained that Broadwell-E is completely drop-in compatible with existing X99 motherboards on the market. That apparently means it’ll work, but it doesn’t mean all of the features work. When I tried to install the required driver and utility for the Turbo Boost Max 3.0, it bombed out because the Asrock X99 Extreme4 board doesn’t support it.

When it’ll be added I don’t know. Intel said support can be easily added through a UEFI update, but it’s up to the individual board vendor to do so. In other words, the numbers you see here for single-threaded tasks, which could be up to 15 percent faster in theory with Turbo Boost Max 3.0.

Very late in the process, I was able to get the chip into an Asus X99 Deluxe II board. That solved most of my problems, but I didn’t have time to re-run all of my tests. The good news is the Turbo Boost Max 3.0 should impact only the single-threaded tests.

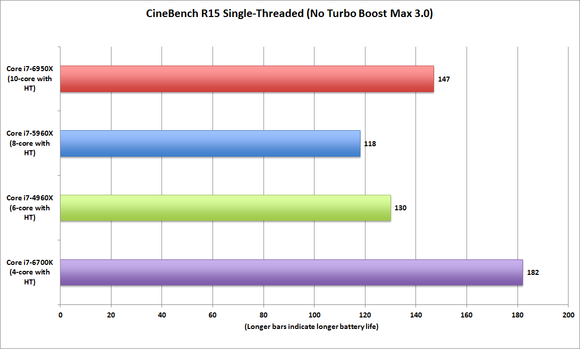

CineBench R15 performance

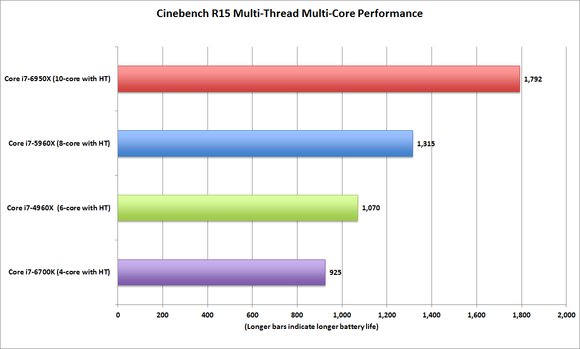

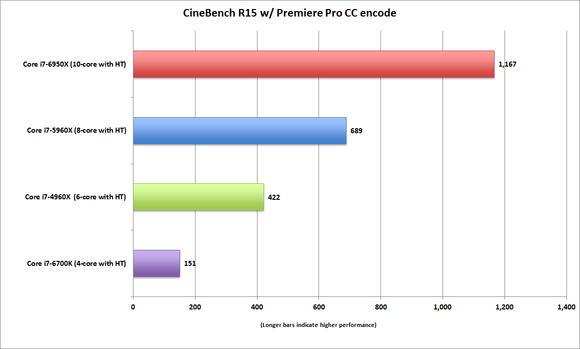

In multi-threaded tests, those 10 cores pay off very nice dividends.

We’ll start this off with a test that’s ideally suited for a 10-core chip: Maxon’s CineBench R15. This is a benchmark based on Maxon’s Cinema4D rendering engine, which the company uses in its commercial products, so you can consider it a reflection of real-world performance.

CineBench R15 loves CPU cores, and the result is pretty monstrous. The Broadwell-E blows past the 8-core Haswell-E chip and stomps the quad-core Skylake chip. You have to give proper credit to that Skylake chip, though: Combined with its state-of-the-art 6th-gen cores and its 4.2GHz clock speed, it really punches above its class.

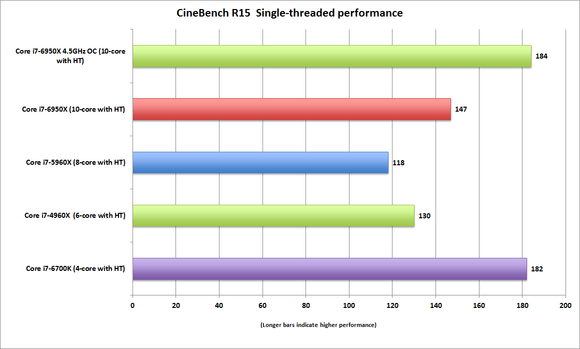

To get a little more insight into how the various CPU cores do when you don’t factor in the difference in core count, I also ran CineBench R15 in the optional single-threaded mode. The high clock speeds plus the newer 6th-gen cores put the Skylake chip in the front seat by a very healthy margin. The Ivy Bridge-E chip does fairly well, but running at a higher clock speed, too.

The worst score comes from the Haswell-E, which I’m going to attribute to its lower clock speeds. Broadwell-E does particularly well at 3.5GHz and this is without Turbo Boost Max 3.0 on.

CineBench R15 in single-threaded performance gives the nimbler, higher clocked Skylake chip the edge.

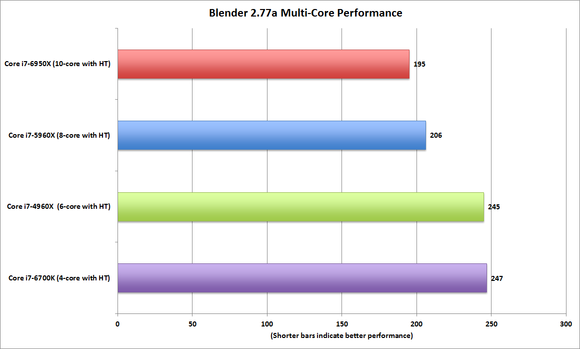

Blender performance

The second benchmark I’m going to detail is Blender, a free and popular 3D renderer used for visual effects by many indie film makers. The test file I used was Mike Pan’s free BMW benchmark file.

The 10-core Broadwell-E still leads the pack, but by less than we expected. I’ve also seen Blender not offer the same core scaling as I’ve seen out of Maxon’s Cinema 4D engine. Going from a dual-core to a quad-core laptop has also shown just average scaling.

The upshot is if you’re working on your indie film project and all the work is done in Blender, you’d be fine with a quad or six-core part. But hey, if you’re an indie filmmaker anyway, you should be working on a shoestring budget, not dropping $1,723 for a CPU.

The popular and free Blender render engine likes multi-core but not quite as much as Maxon’s engine.

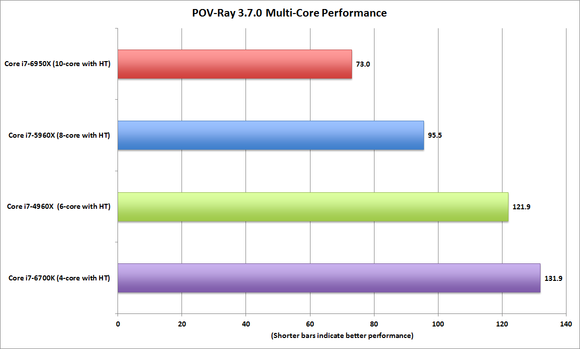

POV-Ray Performance

I’ll close out my 3D rendering test section with POV-Ray. This 3D graphics program dates back to the Amiga and is available for free. We see very nice scaling from the 10-core Broadwell-E. Probably enough to warrant the expense if you really are doing POV-Ray projects and your renders are teeth-gnashingly long.

And yet again, that six-core Ivy Bridge-E Core i7-4960X is starting to look pretty moldy against the quad-core Skylake Core i7-6700K chip.

No surprise, POV-Ray also likes 10-core CPUs.

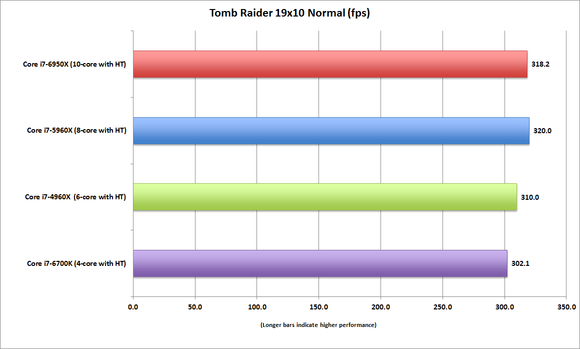

DirectX 11 gaming performance

Let me just get this out of the way by saying that no, in today’s gaming experience, a 10-core CPU doesn’t get you more performance. It just doesn’t. That’s because the vast majority of games don’t exploit all those cores. Even the highly touted DX12 probably won’t whip games into shape for at least another year or two. Still, you want proof so the first thing I’m going to run is the DirectX 11-based Tomb Raider.

Again, all of our tests were run on a GeForce GTX 980 with the same driver. For my runs, I set Tomb Raider at 1920×1080 resolution using the normal preset. For the most part, it’s a tie. The real surprise is how Haswell-E and Broadwell-E pull ahead by a bit. Even the Ivy Bridge-E is technically faster, but let’s not kid ourselves. This is a tie. I could run another six more games, but all you’d see is a tie across the vast majority of games. Gaming is still mostly 80 percent about the GPU.

The lesson here is if your system is primarily used to play one game at a time, you don’t need more than a quad-core chip with Hyper-Threading.

No, you don’t get more performance out of a 10-core chip in gaming but you already knew that right?

DirectX 12 gaming performance

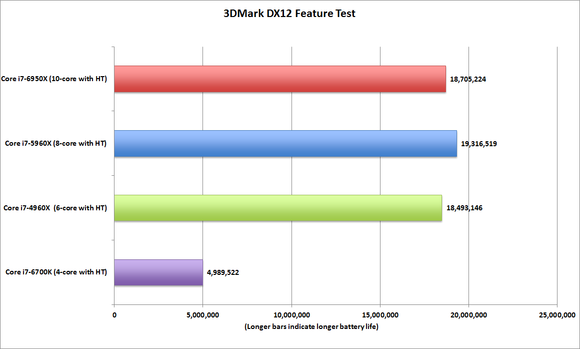

Yes, but there’s that DirectX 12 thing right? You know, the big move from Microsoft to make its gaming API actually exploit the multiple CPU cores we’ve had in our PCs for the half a decade.

To test it I first ran 3DMark’s DirectX 12 feature test. It tests a PC’s ability to issue draw calls or draw objects to a screen. You can see the Skylake Core i7-6700K gasses out at the 5-million-draw call mark. We then see a huge bump to the Ivy Bridge-E chip, and then we basically flatline from 12-threads all the way to 20-threads.

The upshot from the 3DMark DX12 feature test is you don’t seem to really need more than a 6-core CPU with Hyper-Threading.

You can see 3DMark’s DirectX 12 feature test can’t stress more than the 12-threads of our Ivy Bridge-E chip.

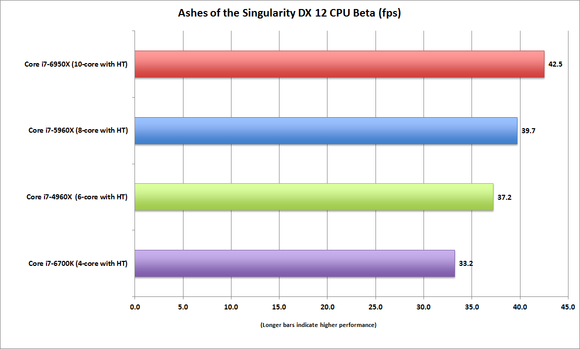

Ashes of the Singularity performance

But what about a real game? To find out I broke out Oxide’s Ashes of the Singularity, a new real-time strategy game that is the showcase title for DirectX 12 performance and draw call capability. Even better, Oxide provided us with a beta version of Ashes of the Singularity that adds a new mode specifically to test CPU performance, rather than GPU performance.

The scene adds a larger map and more complexity using the same engine to push CPUs harder. Oxide said it’s still in the process of tuning the benchmark but was willing to let us run it ahead of time.

The result is certainly a little more promising for the new 10-core. In the return-on-investment category, however, at least at this point in Ashes, it has yet to justify a $1,723 outlay. We’ll plan to revisit this test when it’s finalized.

We got early access to a new CPU focused test in Ashes of the Singularity game to test multi-core performance under DirectX 12.

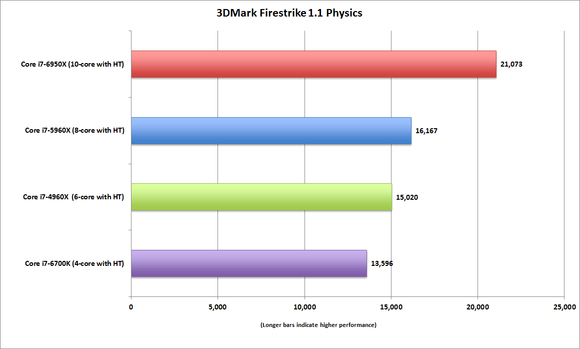

3DMark FireStrike Physics

We’ll close gaming performance with a score from the physics portion of 3DMark FireStrike. It simulates up to 32 threads of game physics using the Bullet Open Source Physics Library that’s also used in such popular games as Grand Theft Auto V and Red Dead Redemption.

Here we see a pretty hefty advantage for the 10-core chip. The surprise is the gap it opens between the 8-core Haswell-E chip.

While it’s a victory for the Broadwell-E, I have to point out that this is a theoretical win, as few game developers are adding enough game physics to actually need 20 threads of computing. If they ever did though, that 10-core would be king.

The physics test in 3DMark FireStrike gives the 10-core a very nice bump.

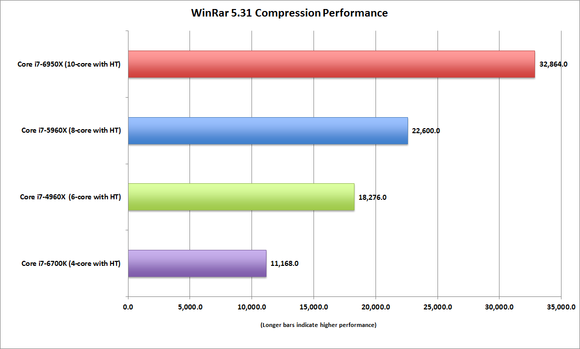

WinRar compression performance

To measure how fast the 10-core chip pushes compression, I used the built-in benchmark in RARLab’s WinRar. WinRar loves lots of threads, and the 10-core Broadwell-E again opens up a can of whup-ass on all others.

The results came as a surprise to me, but if your day job is compressing files in WinRar, a 10-core might be worth it.

If you do lots of compression, you’ll want lots of cores it looks like.

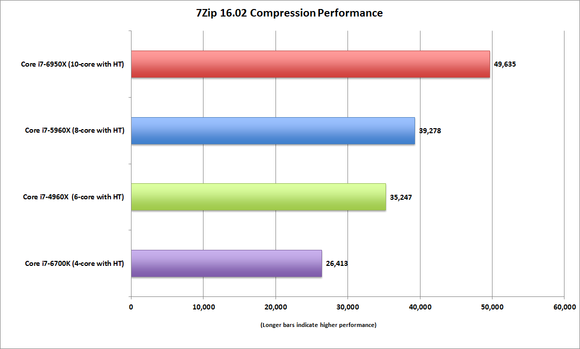

7Zip compression performance

Interestingly, it’s not just WinRar that loves multi-threading. I also fired up the free and superpopular 7Zip compression utility to see whether the WinRar results were fooling my eyes. 7Zip’s benchmark lets you choose the workload based on the maximum amount of threads in the system. For each CPU, I matched the workload to the threads each chip has, so 20 for the Broadwell-E and 8 for the Core i7-6700K. The results, again, put the 10-core well ahead of all others. Nicely done, Broadwell-E.

7Zip loves dem cores too!

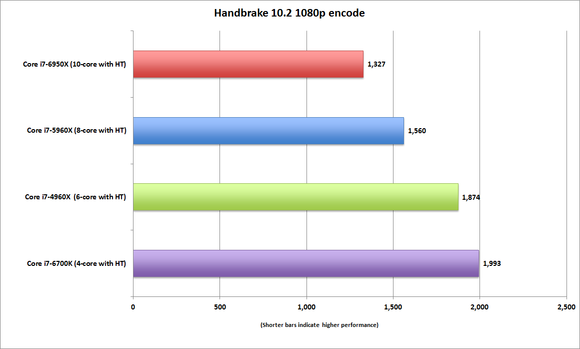

HandBrake 10.2 performance

For our encoding test, we take a 30GB 1080p MKV file and transcode it using the free and superpopular HandBrake utility. Our target file format and size uses the Android tablet preset. The results here put the 10-core Broadwell-E in front, but I’m actually disappointed a tad. Sure, you shave off a serious chunk of time in an encode, but that Core i7-6700K is close behind.

Handbrake 10.2 likes cores but our workload doesn’t seem to stress it as much.

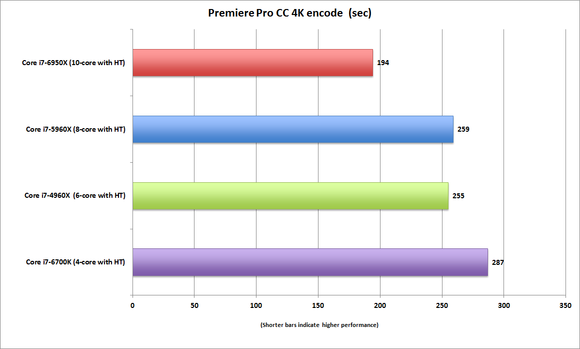

Premiere Pro Creative Cloud performance

For a video test, I used Adobe’s Premiere Pro Creative Cloud video editor. It’s a hugely popular video editor with professionals and prosumers. Premiere Pro supports both GPU and CPU encoding, but to find out which CPU was the fastest, I opted for CPU encoding. The workload was a 4K project Intel provided. I tried using an actual working project created by our own video team .but I found the 1080p video from our Canon C100s didn’t push our CPUs hard enough, with all four chips finishing our encode nearly at the same time.

Intel’s test files increase the resolution to Ultra HD 4K and are a bit more work. The result though, isn’t all that impressive. The Broadwell-E is the fastest, but that quad-core Skylake does pretty well considering its core count. Oddly, the 8-core Haswell-E underperformed too—I’m not sure why, but multiple runs all produced the same result. One theory is the Ivy Bridge-E chip can run up to 4GHz, while the stock Haswell-E clocks in around the low 3GHz range. Perhaps this workload favors the higher clock speeds of the Ivy Bridge-E chip and really doesn’t need more than 12 threads to run. The overall win still goes to the Broadwell-E by a healthy amount, but I expected more.

caption goes here

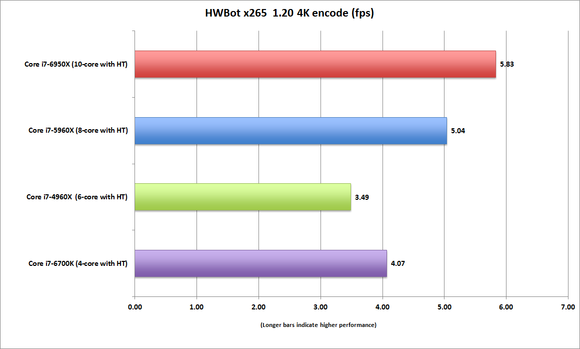

HWBOT x265 performance

For my second encoding test, I decided to throw HWBot x265 at my test CPUs. It’s a test created by Czech overclocker Havli and is built around an open-source x265 encoder. It’s a punishing test. It loves CPU cores and supports numerous modern advanced instruction sets such as AVX2 and FMA3.

The 10-core wins this again quite handily. The interesting side note is even though the Ivy Bridge-E has more two more cores than the Skylake chip, the newer instruction sets and efficiency of the 6th-gen chip appear to give it a nice edge.

How good is that result? Not bad. The world record at overclocking enthusiast site HWBot.org is held by Slinky PC, who hit 12.59 fps using a 22-core Xeon E5 2696 V4 chip, apparently overclocked to 3GHz.

Caption goes here

Megatasking performance

Even though the new 10-core Broadwell-E is a monstrous chip in many multi-threaded apps, you may be disappointed that it doesn’t just wail on the quad-core Skylake chip by huge margins. It does, after all, have six more cores inside.

For one, it has a lower stock clock speed. Overclocking the Broadwell-E gets both within spitting distance; but on multi-threading, that Skylake chip will hang in there in most apps that just can’t use all the cores on the 10-core Broadwell-E.

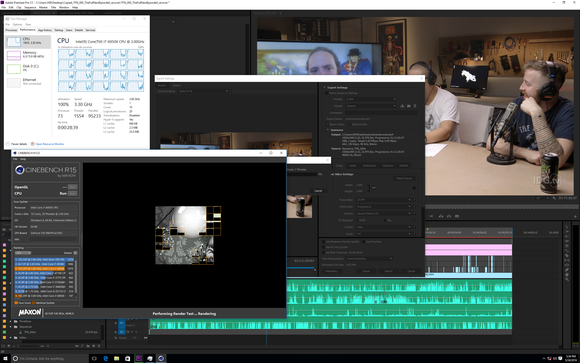

So what happens if you throw multiple tasks at it simultaneously? To find out I fired up Premiere Pro CC again and began rendering out a one-hour 1080p video. I then went ahead and ran CineBench R15 on all four chips.

The 10-core Broadwell-E is great—if you happen to like to do multiple, multiple compute heavy tasks simultaneously.

The result is probably more in line with the beat-down you would expect from a 10-core chip compared to that quad-core. While rendering on the quad-core Skylake, the CPU was running at near 100 percent capacity. The 10-core Broadwell-E under the same load was cruising along at 55 percent. The quad-core Skylake chip, in fact, was so slow that I was able to run CineBench R15 three times on the Ivy Bridge-E before the Skylake chip finished running it once. So take that, Skylake!

The upshot is you can run a 4K Premiere Pro CC encode while running another one or two content creation apps without seeing everything grind to a halt, like it would with a quad-core.

Is this realistic? For a content creation person or what Intel calls a “megatasker,” yes. Most people start heavy compute tasks and take a walk around the block while it finishes. With the 10-core Broadwell-E you could keep working. If time is money, the 10-core chip is the natural choice.

It’s hard to occupy all the threads available on a 10-core chip unless you megatask it.

Next up: Conclusion and Overclocking

Intel

IntelHow does it overclock?

I’m always a little hesitant to issue proclamations of how a new CPU overclocks based on a sample of one. Many times it’s not about the overclocking capability of the chip, it’s about the overclocking capability of the overclocker.

Intel itself, as usual, won’t say anything about what to expect. That’s understandable, as overclocking is usually a crap shoot. I can at least relate my own experiences.

First, I’d say it depends on the motherboard. The Asrock X99 Extreme 4 on which I ran most of my stock clock tests was a dismal fail. I couldn’t push the chip much beyond stock and gave up after wasting an hour trying to get minimal overclocks out of the chip.

Very late in my review though, I received an Asus X99 Deluxe II board. A newer motherboard that supports Turbo Boost Max Technology 3.0.

With the Asus X99 Deluxe II board, I dialed up a 4GHz all-core, ratio-based overclock and booted into the OS. No muss, no fuss. That’s without having to mess with voltage either.

That’s really not bad, and I’ll be the first to say I am not even remotely an extreme overclocker. I didn’t do a formal stability test, but I was able to run numerous multi-threaded benchmarks without issue for several hours. I then overclocked the “best” core up to 4.5GHz and used Turbo Boost Max 3.0 Technology to bind particular applications to it.

Overall, I’m pretty happy my sample overclocked on the Asus X99 Deluxe II. Not so on the Asrock.

But what should you expect? It’s still very early in the life of this chip. After speaking to various motherboard and system vendors, it sounds like you should expect at most 4.2GHz to 4.3GHz overclocks on all 10 cores. Beyond that, I’m told, it gets difficult to manage the heat and voltage. Its predecessor, Haswell-E, generally ran out of gas at 4.5GHz in practical use, so Broadwell-E seems to be within expectations.

You may recoil at the thought of loosing a little overall overclocking head room, but the greater efficiency of Broadwell cores over Haswell cores make up for it.

Broadwell-E cores running at 4.5GHz pull even with Skylake cores running at 4.2GHz.

Conclusion

First, I’ll sum up the performance aspects of the 10-core Broadwell-E by saying, damn, it’s a freaking monster. In multi-threaded tasks it easily thrashes the 8-core Haswell-E. Combined with per-core overclocking and Turbo Boost Max 3.0, it can hang with the nimbler Core i-6700K chip in lightly threaded and single-threaded tasks, too.

That’s a win no matter how you cut it. Intel said it aimed to give you the best of both worlds for multi-threaded and lightly threaded, and it has achieved that.

The elephant in the room is that $1,723 price tag.

Okay, it’s actually a little cheaper in stores.

Intel Core i7-6950X Processor Extreme Edition

Price When Reviewed:$1743.00Best Prices Today:$499 at Amazon

Price When Reviewed:$1743.00Best Prices Today:$499 at Amazon

Initial rumors last year indicated the 10-core chip would slot in at the same $1,000 price of the 8-core Haswell-E. A grand may seem excessive but if you got the 10-core version for the price Intel used to charge for an 8-core, it’s like getting “free” stuff.

Intel actually did just that when it replaced the $1,000 6-core Core i7-4960X with the $1,000 8-core Core i7-5960X chip. Intel isn’t giving away any freebies this time though.

At the price Intel wants, you could actually buy a 14-core Xeon. That Xeon, though, would probably be even more overkill and would not give you the single-threaded performance of the Core i7-6950X.

As it stands, the Core i7-6950X is easily Intel’s most powerful consumer chip that it’s ever made by a long shot. I just wish it were actually affordable.

Intel

Intel