The 13 most momentous security stories of 2014

Image: maxkabakov / Thinkstock

Image: maxkabakov / Thinkstock

A year to forget

Epic hacks, major vulnerabilities, and other security surprises rolled across the Internet like a tidal wave in 2014. We thought we’d seen it all after an SSL vulnerability pierced the heart of the Internet and the crypto world lost a major asset. But then Sony (once again) fell prey to one of the most devastating cyberattacks ever.

Beyond major hacks and tragedies, there were also positive developments. Google and Yahoo got serious about email crypto, Android and iOS beefed up their encryption, and Tor won a major supporter.

Here are the top security stories of 2014—at least so far. With a few days left in this wacky year, you never know what could happen.

Sony Pictures hack

In late November, a hacker group calling itself the Guardians of Peace (GOP) took over the computer network for Sony Pictures and locked employees out of their PCs. The group also snatched a treasure trove of sensitive data and dumped much of it online.

Over the following weeks, GOP made several strange demands, including “equality” for Sony employees and a halt to the release of The Interview, a movie (pictured at left) about an assassination attempt on the leader of North Korea. Authorities initially doubted but now believe the attacks and threats emanate from North Korea itself.

A reeling Sony finally decided to cancel the film’s premiere, citing terror concerns.

Goto fail

Apple’s even a trendsetter in security vulnerabilities, it seems. In February, the company fixed the ‘goto fail’ bug, an SSL vulnerability that reared its head before Heartbleed and the GNUTLS bug, two other massive SSL-related woes discovered in 2014.

Unpatched, ‘goto fail’ could allow an attacker to capture or modify data that was supposed to be encrypted via SSL/TSL. The vulnerability affected OSX and iOS devices and was caused by a one-line typo in Apple’s code—proving that even when it comes to bugs Apple can’t help creating something that is simple, effective, and elegant.

Heartbleed

Heartbleed, revealed in April, was the first of two major vulnerabilities that rocked the Internet in 2014. The bug allowed attackers to snatch sensitive data from servers running OpenSSL. Heartbleed worked only if the server had a special OpenSSL feature called “the heartbeat extension” enabled. A hacker with knowledge of the vulnerability could grab all kinds of data, including SSL site keys, usernames and passwords, email, instant messages, and files.

Heartbleed forced millions of people to change their passwords across a variety of websites. Although Heartbleed can be fixed with a quick software patch, security researchers say Heartbleed will remain with us for years to come. The risk is highest with smaller sites that haven’t yet bothered to update their server software.

Shell shocked

Mere months after the Internet finished congratulating itself on fixing the problems associated with Heartbleed, another major vulnerability appeared. Dubbed Shellshock, the flaw was in the Bash shell, a standard component on any Unix-y systems like Linux and OS X, as well as web servers and home networking equipment. Shellshock allowed hackers to run critical shell commands on an affected machine. Security researchers even found examples of Shellshock being exploited in the wild.

Experts consider Shellshock to be a much bigger problem than Heartbleed, because it allows such devastating access to a target machine and affects a far broader range of devices.

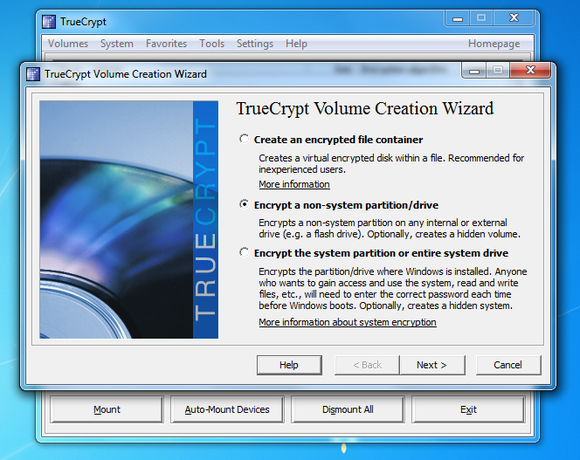

The death of TrueCrypt

The sudden disappearance of one of the world’s most trusted and revered encryption programs inspired all kinds of conspiracy theories in May. Did the creators swallow some kind of poison pill to alert the world to shenanigans by the feds? Was it a hoax perpetrated by hackers? Was it connected to the crowd-sourced security audit? Nobody knew for sure.

Seven months later, TrueCrypt is still gone, and the software’s original still URL redirects to a SourceForge page warning of potential security vulnerabilities. The page also recommends that Windows users switch to Microsoft’s homegrown BitLocker, though there are other encryption options available.

PGP for all

PGP/GPG is a proven, secure solution for encrypting email, but it’s notoriously difficult to use. Google began a project to fix that issue in June—End-to-End, a PGP implementation for Gmail via a Chrome browser extension. Yahoo followed up in August announcing that it would adapt Google’s plugin for Yahoo and roll out encryption for Yahoo Mail in 2015.

The mainstream introduction of email encryption was largely inspired by the fallout from the Snowden leaks about NSA snooping. But not everyone thinks PGP is the best idea for mainstream services. Shortly after Yahoo’s announcement, Matthew Green, a cryptographer and research professor at John Hopkins University, argued that PGP should be replaced by a more modern and user-friendly system.

Mobile crypto

Apple and Google also became more serious about encryption, beefing up iOS and Android, respectively. Apple caused waves when it closed a backdoor for grabbing data off an iOS device to comply with lawful warrants. The change made it impossible for anyone but the iPhone or iPad’s owner to decrypt the device.

Google also decided to enable encryption by default on devices that come with Android 5.0 Lollipop. Android has had optional device encryption since Android 3.0.

Looking at a future of user-controlled mobile device crypto, FBI Director James Comey argued publicly on several occasions that Apple and Google were enabling kidnappers and terrorists.

Tor in the news

The so-called darknet hidden inside the anonymizing Tor network made numerous headlines in 2014. The fascination really started in 2013, with the demise of The Silk Road and the arrest of its operator, Dread Pirate Roberts. But in 2014, law enforcement was suspected of actively exploiting flaws in the network and took down several criminal sites in November.

Meanwhile, Facebook gave the legitimacy of Tor a boost, reminding the world that the anonymous network is more than a mere haven for criminal activity by rolling out a Tor version of the social network. The social network even managed to be the first Tor site to receive its own SSL certificate.

Extra Google juice for encrypted sites

Hoping to help make the web more secure for users, Google in August announced that any site that enabled SSL/TLS encryption (HTTPS) would get a small boost in its search rankings. SSL/TLS encrypts the connection between a user’s device and the website they are viewing. Encrypting as much web activity as possible became an important consideration following the revelations in 2013 that the National Security Agency was snooping on Internet user activity all over the world.

BadUSB

Berlin-based Security Research Labs revealed in July that USB devices like thumb drives suffered from a fundamental vulnerability that made it possible to turn them into an unstoppable malware delivery system. The culprit was the firmware on these devices, which was unprotected and reprogrammable by attackers. This flaw could be used to execute malware, or make a thumb drive behave like a keyboard and enter key presses.

Hoping to force USB device makers into action, two researchers publicly released a set of tools in October that would enable hackers to create badUSB exploits.

Wirelurker, Apple attacker

In November, researchers at Palo Alto Networks discovered a piece of malware dubbed Wirelurker designed to collect call logs, contacts, and other sensitive data from iOS devices. The malware gets onto iOS devices when the device connects to an infected PC, trying to infect an app on the target device. Unlike most iOS malware, Wirelurker could even infect devices that weren’t jailbroken.

Apple quickly addressed Wirelurker, blocking apps infected with Wirelurker from running. In mid-November, Chinese authorities shut down a site connected to Wirelurker distribution and arrested three people suspected of developing the malware.

Verizon’s unstoppable perma-cookies

Verizon was caught tampering with subscriber web traffic traveling over the company’s mobile network in October. Hoping to beef up its mobile advertising business, Verizon would insert a unique identifier, called a Unique Identifier Header (UIDH), into a user’s HTTP requests. The UIDH could be used to identify a specific device and was being used by third parties with the potential goal of building user profiles on Verizon subscribers.

Because Verizon’s UIDH scheme was injected on the server side, users could do little to block it other than sticking to Wi-Fi networks, or using HTTPS or a VPN whenever sending web traffic over Verizon’s mobile network.

1.2 billion alarmists

In August, reports claimed that hackers in Russia had control of a massive database of user names and passwords topping 1.2 billion entries. Hold Security, the company that discovered the breach, declined to say which sites were affected.

Security analysts started asking questions, though, and the stolen database story started feeling a little bogus—especially when Hold Security was accused of holding back data about the breach and using the subsequent panic to turn a profit.

In the end, the consensus conclusion was that the database was probably amassed from several breaches over a long period of time, and many of the logins weren’t even valid anymore.